MCC PROGRAMMATIC PROCESS

Turning Science Into Collaborative Action

Guided by foundations in social sciences, the MCC program directly supports communities confronting the impacts of climate change and other complex “adaptive challenges” through knowledge co-production (O’Brien and Selboe 2015). By cultivating relationships and understanding the needs of the community, and then working together to develop useful products, we are helping communities to adapt and build resiliency.

Dive deeper: MCC Approach

The knowledge co-production process can be applied in any location and at any spatial, organizational, or practitioner scale. Our program focuses on manager networks that are accountable to specific landscapes and seascapes on Hawaiʻi Island and that are accountable to the human communities that utilize the natural resources within these landscapes. As the scientific process, research output, and long-term professional networks increasingly root within the needs, values, identities, and practices of specific places, these pathways and networks increasingly expand the capacities of adaptation, resilience, and sustainability within local communities.

Dive deeper: Manager Context

MORE MCC

QUICK LINKS

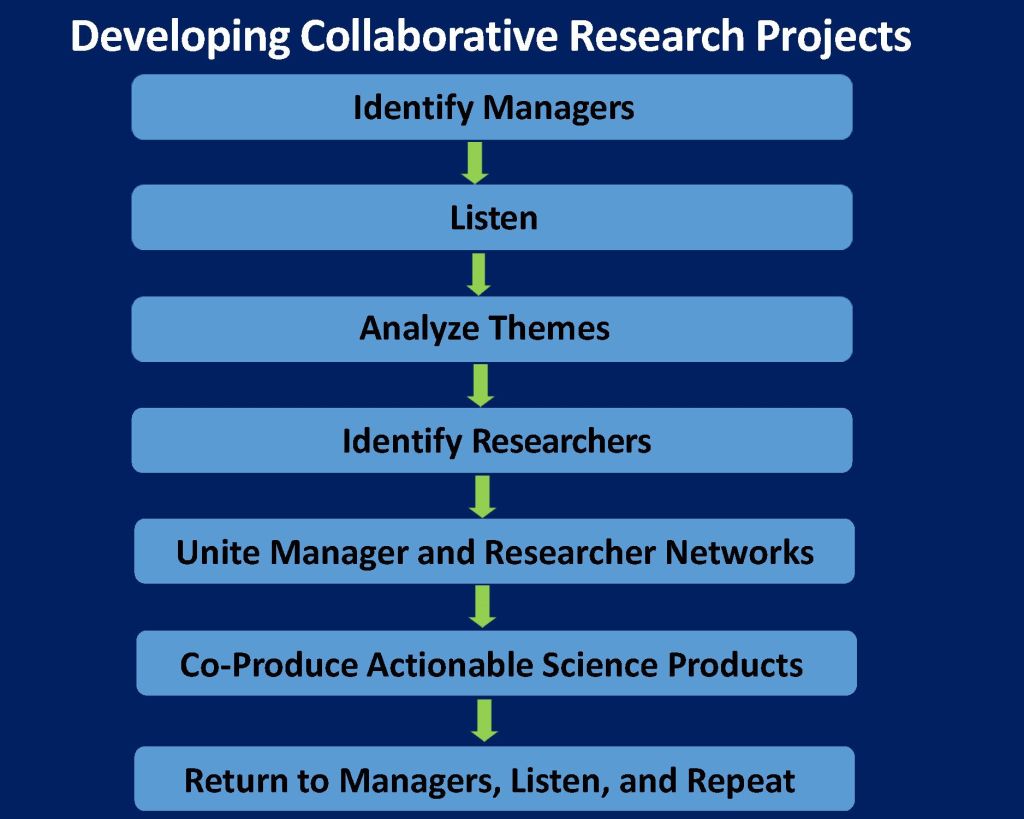

MCC employs the following three steps as we engage with communities through the process of knowledge co-production:

In 2015, the Manager Climate Corps began searching out existing long-term local professional networks that would create the MCC’s foundation and guide its climate research efforts at UH Hilo (see Manager Needs Assessment). Understanding the needs of diverse local professional networks would guide our subsequent knowledge co-production and networking efforts and the types of products that result.

The MCC foundation was deliberately built on sustained, long-term, and in-person interaction with local managers. By focusing on iterative, growing relationships, rather than a momentary needs assessment, the MCC can maintain support for local professional networks through time by sustained understanding of individual managers’ perceptions, norms, values, needs, information sources, and experiences—collectively their worldviews.

While there is a national focus on conducting “stakeholder-driven” science, managers, decision makers, practitioners, and end users are frequently poorly defined and management scales not clearly outlined. Therefore, we chose to connect with individuals whose positions are largely focused within Hawaiʻi Island and who are directly accountable to explicit areas of land, water, and the surrounding communities that utilize the managed natural resources.

The Manager Climate Corps network is comprised of local managers across a variety of organization levels (e.g., county, state and federal government, NGOs, and private land managers), as well as a diversity of management sectors that may be influenced by changing climate (e.g., county planning, agriculture, and infrastructure).

We continue to locate, engage, and build upon existing professional networks in order to the address the diverse array of emerging climate adaptation issues on Hawaiʻi Island. This program is inclusive of wide-ranging management perspectives in native ecosystems (terrestrial and marine), traditional cultural sites, traditional cultural homelands, marine recreation, near-shore harvesting, transport and safety, ranching, agriculture, county planning, community-based management, fire hazards, and invasive species.

Dive deeper: Manager Needs Assessment

Read more: Environmental Management publication, Needs Assessment report (PDF)

The Manager Climate Corps program hosts co-knowledge co-production workshops led by natural and cultural resource managers in order to engage with all interested UH faculty and federal researchers. These workshops initiate an extended proposal request process that requires existing relationships between scientist and stakeholders to initiate a research pathway. Meetings hosted in 2016 and 2019 were well attended by diverse researcher representation, including sociology, Hawaiian studies, anthropology, geography, environmental engineering, environmental economics, marine sciences, and ecology.

The MCC program staff presents our knowledge co-production process and participant resource management groups from around the island and from ridge to reef present their organizations’ research needs in relation to climate change adaptation. The second half of the meetings are dedicated to round table discussions exploring possible collaborative research projects, workshops, and coursework development at the university. Four formal calls for manager-driven research project proposals were distributed university-wide and across manager networks as a result of these collaborative workshops.

The faculty-manager roundtable discussions can lead to funding of manager-driven graduate research projects covering a wide range of interests. For example, a 2016 project initiated from workshop discussions was published as a case study in the US Climate Resiliency Toolkit. Because managers are co-leading each research project from inception to completion, the research products have a higher likelihood of being readily put to use and shared with broader professional networks on Hawaiʻi Island and beyond.

Dive deeper: MCC FY2016 Research Projects

Read more: A case study in the US Climate Resiliency Toolkit

The Manager Climate Corps (MCC) program organizes interactive forums where the large and diverse collection of MCC members from the above research and management collaborations work with MCC staff to organize unique engagement experiences.

In 2016, this network held a three-night, four-day climate change immersion camp bringing together managers, scientists, traditional Hawaiian cultural practitioners, graduate students, and policy professionals. Attendees collaboratively discussed current and near-future needs for adapting to local climate change impacts around the themes of knowledge co-production, multiple ways of knowing, and place-based adaptive management. The camp took place outdoors amid endemic forest species at the Kiolakaʻa Ranger Station in Kaʻū and showcased our four manager-led graduate research projects as collaborative examples for other participating professional networks. Post event surveys indicated a strong interest in further developing diverse professional networks as a mechanism of building local capacities of resiliency, adaptation, and sustainability in the face of global change.

In the years following the immersion camp, the MCC has also developed a number of diverse interactive conference forums locally, regionally, and nationally. The forums are all focused on building adaptive capacity, knowledge co-production, and growing strong in-person networking opportunities between graduate students, scientists, and managers. Forums have utilized a variety of formats (film, panels, small group discussions, and presentations) and are opportunities to interactively participate in uniting multiple knowledge forms and distinct worldviews through professional networking opportunities. Groups in these events typically discussed the application of knowledge co-production on the ground.

By drawing diverse backgrounds, in-person forums such as these are unique opportunities for researchers, managers, and the next generation of professionals to develop relationships, deepen understanding across worldviews, expand networks, develop actionable products, and, thereby, build upon human capacities of adaptation, resilience, and sustainability through times of significant socio-ecological change.

Dive Deeper: 2016 MCC Climate Change Immersion Camp

Check out our other forums: MCC Events

Manager Context

MANAGER TYPES

Examples of managers involved in MCC networks: ranchers, farmers, traditional native Hawaiian managers of biocultural resources, fire managers, coastal managers, infrastructure planning and development professionals, managers of native marine and remnant terrestrial ecosystems, and invasive species managers.

MANAGER SCALE

Spatial Scale

While knowledge co-production can be utilized at any geographic, organizational, or political scale, we focus on a specific spatial scale: Hawaiʻi Island (managers and policy professionals primarily focused on Hawaiʻi Island). Managers can be site-specific, focused on larger watershed/moku scales, or island-wide (Winter et al. 2018). The central requirement is direct and regular involvement within and, therefore, accountability to a specific, well-defined landscape or waterscape as well as accountability to the communities (group norms and values) that utilize the natural resources within the area. In this manner, MCC pathways are rooted by local manager networks.

Organizational Scale

MCC projects and events include a wide range of organizational scales, including non-governmental organizations as well as federal, state, county, and for profit organizations.

MANAGER ROLES

Custodians of Context

Context from local managers as co-leads in research pathways is vital to achieve increased implementation of research products, which is in turn paramount in supporting societal capacity for adaptation. Field managers and local decision makers function as custodians of context in the socio-ecological systems in which they are embedded. Informed by their regular experiences in the places they influence and are influenced by, field practitioners are immediately accountable to an explicit extent of land, water, and communities of people (Brown et al., 2012; Laursen et al., 2018).

Multiple Ways of Knowing

MCC projects emphasize and integrate multiple knowledge forms and the union of distinct worldviews by supporting diverse networks of natural resource managers, cultural practitioners, policy professionals, social scientists, climate scientists, and biological scientists (Laursen et al., 2018; Ingold, 2011). The phrase “multiple ways of knowing” includes logical knowledge forms (articulate knowledge) that result from rational intellect, technical analysis, and reason, as well as intrinsic knowledge forms (tacit, embodied, or situated knowledge) that result from experience, instinct, perception, cultural practice, intuition, and emotion. For specific context on the MCC’s foundations within and utilization of multiple knowledge forms, explore our worldview figure and human dimensions resource library on the MCC Approach page.

Tacit or embodied knowledge is largely experiential and often place-based in that it is achieved through direct person-to-person and person-to-nature interactions. It can be difficult to characterize in explicit form (Dampney et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2012). Though at times challenging to define or quantify, tacit knowledge forms are often stronger drivers of human behavior than articulate knowledge forms (Kahan et al., 2012; van der Linden et al., 2015; Amel et al., 2017). Similarly in relation to intrinsic knowledge, Ingold (2011) states that “information, in itself, is not knowledge, nor do we become any more knowledgeable through its accumulation. Our knowledgeability consists, rather, in the capacity to situate such information, and understand its meaning within the context of direct perceptual engagements with our environments.”

Amel E, Manning C, Scott B, Koger S (2017) Beyond the roots of human inaction: fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science, 356(6335), 275-279.

Brown PR, Jacobs B, Leith P (2012) Participatory monitoring and evaluation to aid investment in natural resource manager capacity at a range of scales. Environ Monit Assess 184:7207-7220.

Dampney C, Busch P, Richards D (2002) The meaning of tacit knowledge. Australasian J of Information Systems Dec. 3–13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v10i1.438

Ingold T (2011) The Perception of the Environment: essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill, 2nd edn. Routledge, London.

Kahan DM, Peters E, Wittlin M, Slovic P, Ouellette LL, Braman D, Mandel G (2012) The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat Climate Change 2:732-735.

O’Brien K, Selboe E (2015) The adaptive challenge of climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York

van der Linden S, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A (2015) Improving public engagement with climate change: five “best practice” insights from psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci 10:758-763. doi: 10.1177/1745691615598516.

Winter, KB, K Beamer, MB Vaughan, AM Friedlander, MH Kido, AN Whitehead, MKH Akutagawa, N Kurashima, MP Lucas, and B Nyberg (2018) “The Moku System: Managing Biocultural Resources for Abundance within Social-Ecological Regions in Hawaiʻi” Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103554