Coastal sewage systems, sea-level rise, and the future health of ocean communities

September 30, 2024

There are approximately 88,000 cesspools across the islands of Hawaiʻi, many located near coastlines and beaches. Roughly 53 million gallons of untreated sewage is released into the ground each day from these cesspools, according to the Hawaiʻi Department of Health. That untreated waste leaches into streams, groundwater wells, and oceans, contributing to illness for swimmers, surfers, and paddlers and harming coral reefs and other marine life. In addition, rising sea levels further compromise the infrastructure and effectiveness of coastal sewage systems.

Hawaiʻi’s geologic landscape is made up of permeable volcanic rock, and an expansive network of cracks, fractures, and lava tubes allows water to quickly move through these systems. With little to no soil to break down the organic matter in cesspool sewage, that wastewater seeps into the groundwater and finds its way to coral reef ecosystems.

Coral reefs, considered rainforests of the sea, are the most biologically diverse marine ecosystems, providing habitat for thousands of reef fish, invertebrates, and other organisms. They also provide food, medicine, recreation, and coastal protection against storm waves and flooding.

When contaminated groundwater infiltrates shoreline ecosystems, it can have dire consequences. Wastewater pollution contributes to excessive concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus in seawater, which fuels macroalgae growth, a fast-growing algae that can smother corals and block out the sunlight they need to survive.

Sewage pollution also threatens human health and can contaminate drinking water sources. Untreated wastewater from cesspools contains bacteria and viruses that can cause illness, infections, and more. According to a 2020 Hawaiʻi Department of Health report, Hawaiʻi has two times more methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections than the national average.

Community, science, traditional knowledge, and government working together

In 2017, the Hawaiʻi state legislature passed Act 125, requiring all cesspools in the state to be converted to septic or other approved wastewater systems or connected to a sewer system by the year 2050. A long-term cesspool conversion plan was developed to identify which cesspools have the greatest potential to impact human health and the environment and to prioritize them for removal.

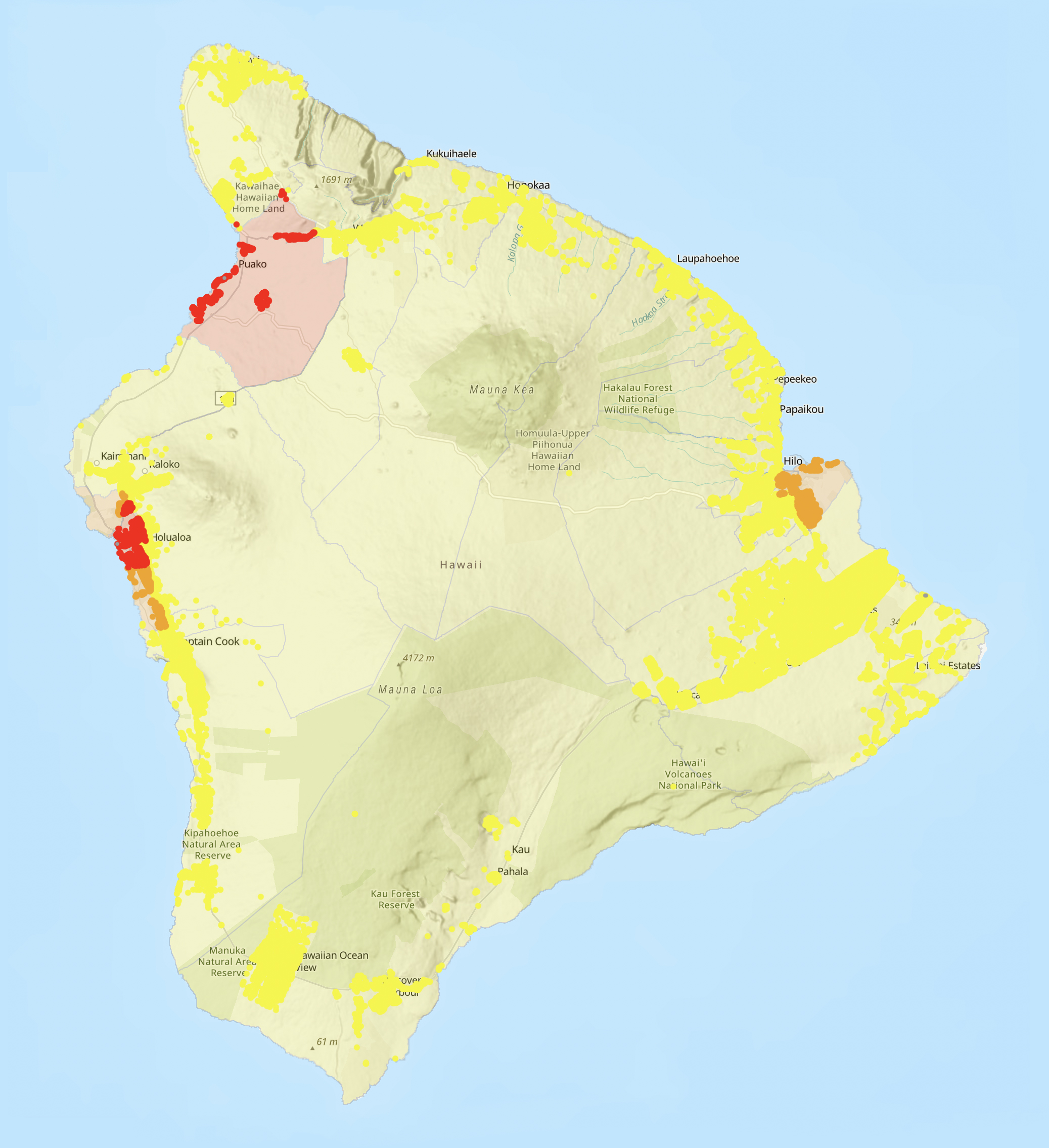

Kahaluʻu Bay on Hawaiʻi Island lies within a priority 2 area for cesspool conversion. However, many cesspools in the area have not been documented and don’t show up in the statewide assessment, so when the statewide prioritization was done, it far underestimated the extent of pollution in the area.

A research project funded by the Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center (PI-CASC) aims to fill that information gap while investigating how sea-level rise will impact sewer infrastructure, cesspools, and water quality along the Kailua-Kona coast. To date, no models of the area have included wastewater systems that could be inundated by rising seas or examined future water quality impacts with observational data.

The research is being conducted, recorded, and analyzed by graduate student Ihilani Kamau through PI-CASC’s Manager Climate Corps (MCC) program. The MCC program emphasizes collaboration across worldviews that unites students, communities, natural resource managers, researchers, cultural practitioners, and policy professionals to develop place-based research and tools to adapt to climate change.

“This project actually started off from the community reaching out, saying that they had some concerns and wanted something to be done about it,” says Kamau.

Kahalu‘u Bay, also known as ‘āina lei ali‘i, or “lands that adorn the chiefs”, is considered a wahi pana, a sacred place abundant in cultural and ecological value, and for centuries it has provided food for local residents and connection to ancestral heritage. Cindi Punihaole, director of the Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center, a program of The Kohala Center, has led conservation and education efforts in this area for more than 15 years.

Punihaole has observed the degradation of coral reefs at Kahalu‘u Bay and has seen high levels of disease and impacts beyond coral bleaching. “It’s difficult when you’re looking at a beautiful bay, not realizing what’s happening under the water,” said Punihaole.

In August 2024, the research team conducted a dye tracer test at Kahaluʻu by dropping a small amount of bright-green, non-toxic dye into a cesspool from a nearby residence. They wanted to see if this dye (and therefore wastewater) from the cesspool would reach the bay and how long it would take. Sure enough, the fluorescent dye emerged from a shoreline spring, and the short time it took—less than 6 hours—was shocking.

“You can’t see what sewage looks like, but if you could see what sewage looked like, that’s what it would look like. And that’s just from one home,” says Steven Colbert, co-investigator of the study and associate professor of marine sciences at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo. Colbert explained, “At this flow rate, for homes within a couple miles of the shoreline, there is not enough time for biological processes to breakdown the sewage, or for dilution of the sewage to occur.”

For Punihaole, the dye tracer test was a revelation that clearly illustrated the pollution entering the bay. “When you go in the water, chances are you’re going to be drinking some of that water, or it’s going into your ears or your nose,” says Punihaole, adding, “The corals are living in that water.”

Planning for the future health of ocean communities

As a graduate student at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, Kamau always assumed she’d be working with fish and corals but had never expected to be studying the water itself. She realized, “As someone who has always loved the ocean, I knew this project was for me, because I knew I could help make a difference with this research. I have always wanted to take care and protect our ocean, so that future generations can grow up loving the ocean the same way that I did.”

Kamau’s project methods include field surveys, sample collection, dye tracer tests, and sea-level rise projections for West Hawaiʻi from Kailua-Kona to Keauhou. Through this research, the hope is that the water quality data and mapping tools from this project will aid in adaptation planning and targeted investment actions for coastal wastewater infrastructure in Hawaiʻi. The team also anticipates that this model can be a template for other locations under similar sea-level rise threats in Hawai‘i and elsewhere in the region.