Assessing the impacts of urban wildfire on coral reefs in Lahaina

March 21, 2025

From the desert-like conditions in west Maui, to the lush rainforests in the east, to the pristine beaches all around, Maui is home to diverse landscapes and microclimates. Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center (PI-CASC) Graduate Scholar Sean Swift grew up in Kula, a largely rural town that stretches across the western face of Haleakalā.

“I spent a lot of time in the ocean growing up. I think because we lived Upcountry, kind of far from the ocean, we’d often spend the whole day at the beach whenever we went. I started surfing pretty young, and, although it’s cliche, I’ve learned so much about the ocean’s conditions and rhythms from that.”

Swift started his academic journey in terrestrial biology and earned an M.S. in biology from California State University. After returning to Hawaiʻi, he decided to change focus to marine biology.

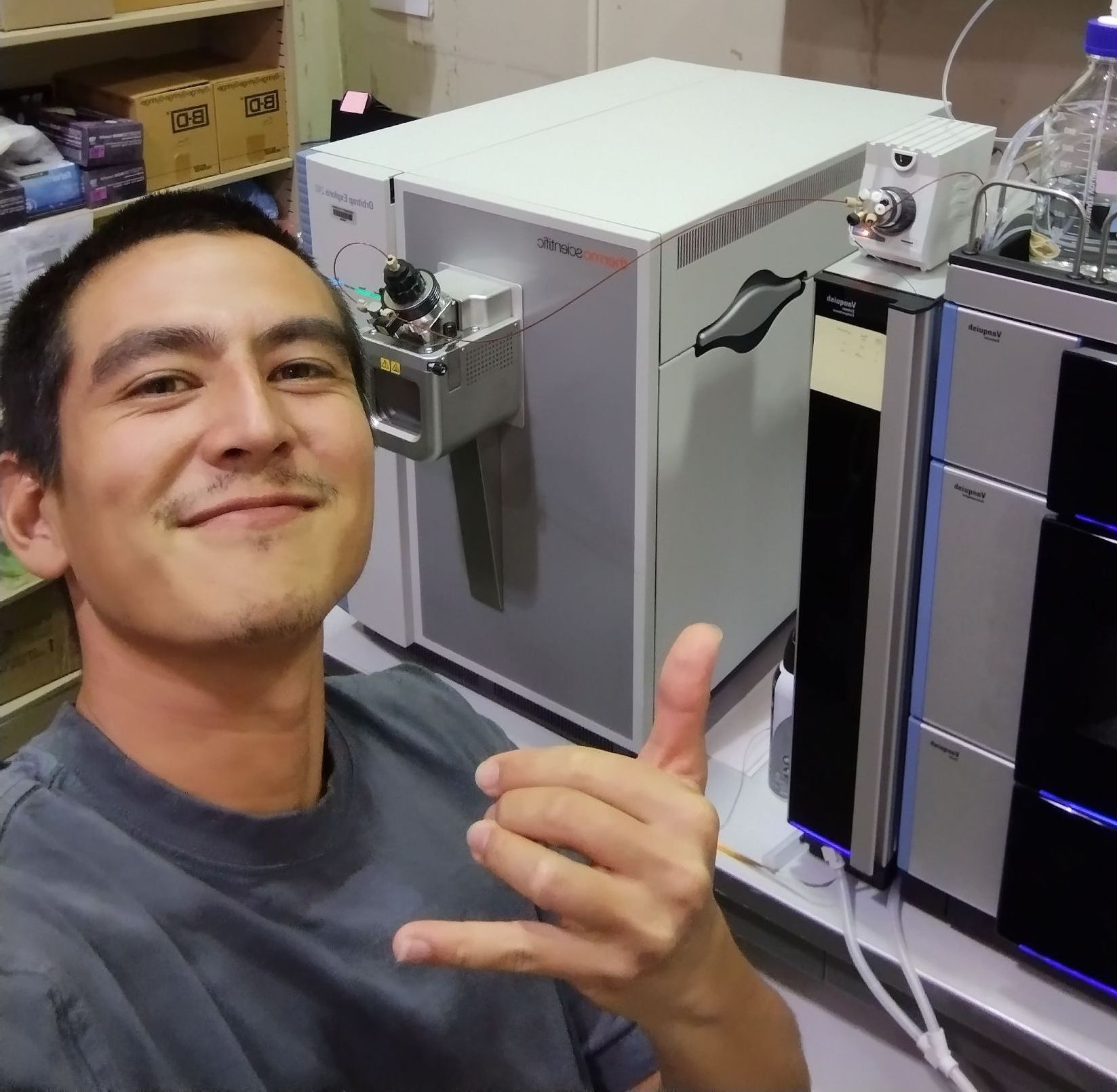

“Honestly, I was drawn to marine biology more for scientific reasons than sentimental ones,” he explained. “I’m drawn to microbiology, and UH has an amazing group of people who work on marine microbes. I wanted to be part of that scientific community.”

Now pursuing a PhD in marine biology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Swift is giving back to his island home through research. He is working with Andrea Kealoha, assistant professor of oceanography at UH Mānoa, on “Effects of climate-driven increases in sediment delivery on coral reef ecosystem productivity and accretion: Developing predictive models for management priorities across Maui,“ a project that aims to understand better how the 2023 Maui wildfires affected coastal waters around Lahaina. In particular, how coral reefs in that area might have been impacted by fire-related chemicals. Prior to this project, research hadn’t been done on the impacts of urban wildfires on coral reefs.

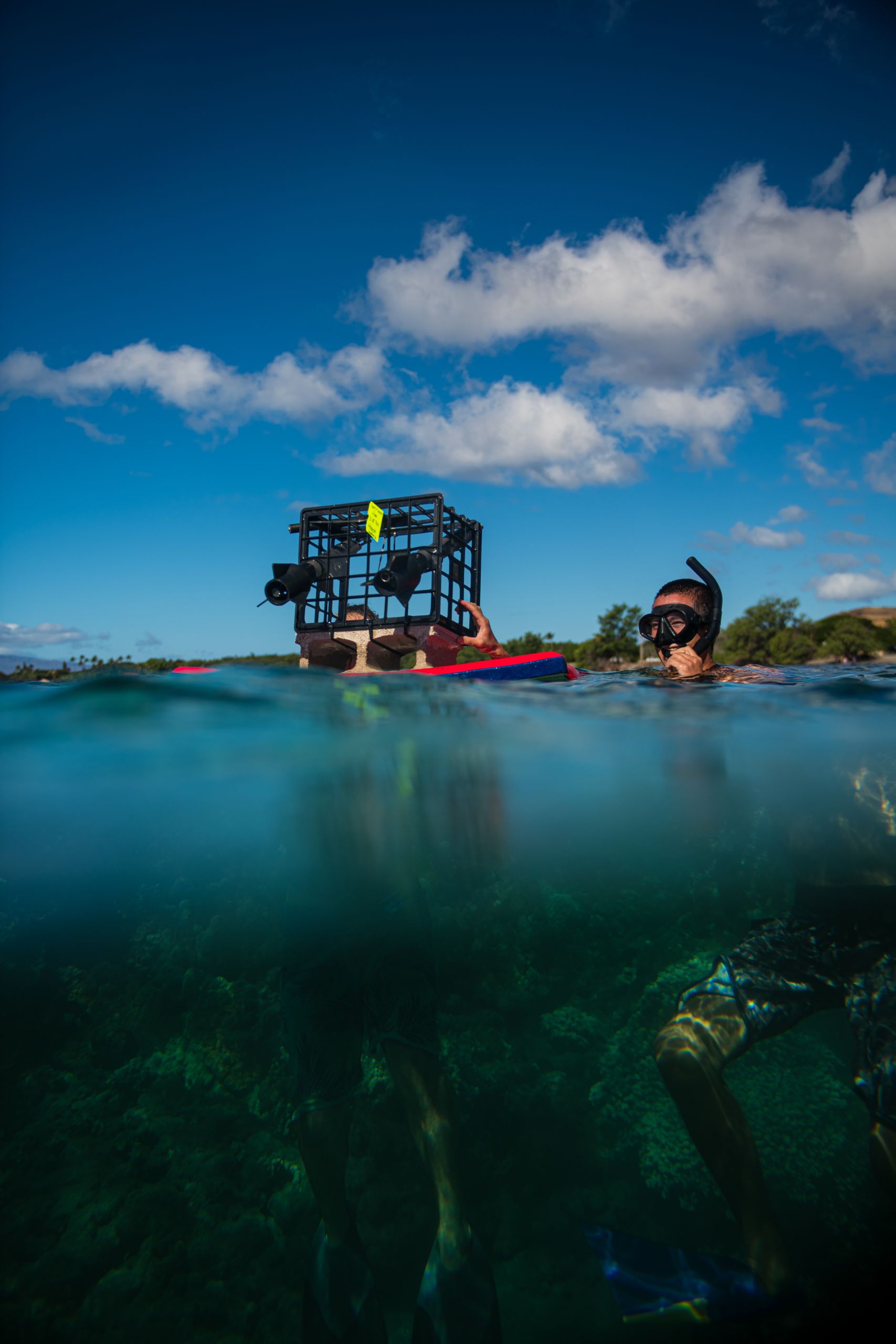

Burned urban infrastructure can introduce chemically complex contaminants to the environment, and urban modifications to surface water and groundwater flow affect the transport of contaminants into the ocean. Swift and the project team measured a broad suite of water quality parameters, including inorganic nutrients, trace metals, dissolved organic compounds, microbial community composition and abundance, and carbonate chemistry.

“Perhaps the most important result is that we did not see high levels of any of the especially harmful contaminants we were looking for,” explained Swift. “At the beginning of this project, we feared that we would be documenting a substantial impact on marine ecosystems. While we saw some changes in certain water quality parameters, like dissolved copper and organic carbon, we did not see evidence of acute toxicity in any of the coral reefs that we were studying.”

Although they did not uncover strong negative impacts, the researchers are finding the science helpful in understanding how things like copper and organic carbon are moving around in the water and affecting reef ecosystems in subtle ways, such as changing microbial communities.

The project is part of an ongoing effort by researchers at UH, who are working closely with a multi-agency consortium based on Maui, including non-profits, community members, the County of Maui, as well as state and federal agencies.

“We made direct connections with local fishers, who helped us collect target species for contaminant monitoring. For me, one of the best parts of this project has been sampling at Mala Wharf, where we have built relationships with the locals who are there every day. We get to catch up with them, share what we’re finding, and they help us by keeping an eye on the sensors we deploy,” said Swift.

The results from this study will help with future resource management decisions and the broader scientific community since so little is known about how coastal urban fires can affect the ocean.

“My hope is that the people of Maui, especially Maui Komohana (West Maui), will benefit the most. I want them to have as much information about their coastal water as possible,” said Swift.