New PI-CASC funded study published in Journal of Biogeography

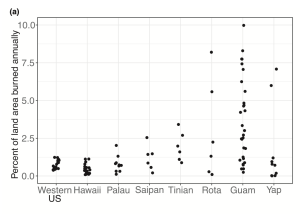

A 2023 region-wide study funded by the Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center (PI-CASC) revealed that areas burned in Micronesian islands, proportional to the total land area, often exceed those burned in the western United States and Hawaiʻi. The study was led by Dr. Clay Trauernicht, Fire and Ecosystems Specialist, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and project leader for the Pacific Fire Exchange. The findings were recently published in the Journal of Biogeography.

Trauernicht and colleagues examined fire records, plant life, and soil maps to determine how climate, past human activities, and fires were connected on nine Micronesian islands spread over roughly 2,000 miles in the Pacific Ocean. The areas burned by fire on these islands, relative to the total land area, can significantly exceed even the western U.S. and reflect how much open savanna vegetation is on the islands.

Guam, in particular, experiences significant wildfires. The study revealed that Guam had the highest rates of land area burned and the number of fires per year, with up to 10% of the island burned during the 1997-98 El Niño and nearly 2,000 fires during peak fire years. “Strong El Niños typically result in more intense drought across the region, increasing the risk and impacts of fire,” said Abby Frazier, co-author and Clark University climatologist.

The islands most prone to fire are those located further west, which experience distinct annual dry seasons caused by monsoonal rainfall patterns. This includes Guam, Palau, Yap, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Conversely, islands further east, such as Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae, which receive wet conditions year-round, have fewer extensive savannas. This research holds practical significance as quantifying the factors that drive fire is a crucial initial step in assessing and predicting fire risk, particularly in regions like Micronesia, where investment in fire science is limited.

As efforts are made to establish more infrastructure to support fire science, consulting local knowledge holders provides valuable insights into the area’s historical fire regime and fire practices. The available evidence suggests that the current patterns of savannas across these islands’ landscapes were created by people through burning. “Fire is entwined with human history and cultural history,” Trauernicht said. “Almost all ignitions on Pacific Islands are human-caused, since lightning strikes are relatively rare.”

Current ideas of fire and controlled burning in the Pacific have been largely shaped by the influence of Western scientists. “Western scientists often look at the greater biodiversity in Pacific Island forests and depict savannas as ‘degraded,’ which implies everything should be forested. But, when you speak with people from that area, you learn that they value the savanna aesthetically, for ease of movement, and for medicinal purposes,” he said. Historically, traditional burning practices in which fire is deliberately and skillfully set were used by indigenous communities worldwide to manage vegetation for various purposes. Trauernicht’s research also suggests that controlled fire settings played a role in land maintenance across the Micronesian islands.

Fire management could potentially include utilizing controlled fire to destroy non-native grasslands that may become fuel for high-intensity fires. However, there is a lack of tools and infrastructure across the Pacific Islands to support controlled burning safely. “There’s been important changes in the context of burning on all these islands – invasive grasses, intense droughts, changes in where people live. It’s so critical that we learn as much as we can from people who still maintain a knowledge of burning about when and where it’s appropriate to use fire. Of course, we also have to ensure we’re working with fire responders and providing resources to adequately protect the things we care about,” said Trauernicht.

For now, Trauernicht hopes his research will shift our thinking about fire and its role in fire management and land maintenance. “How we address fire management now has to incorporate local views to effectively support fire management projects.”