IN THIS SECTION

What is Coral Bleaching?

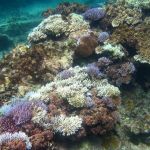

While corals do feed directly from their surrounding waters through filter-feeding tentacles, most of their energy comes from the zooxanthellae. The relationship is mutual: the algae are protected and absorb carbon dioxide from the coral to use in photosynthesis, and in exchange, the coral receives oxygen and other nutrients, as well as their color. So when the zooxanthellae are expelled, the corals appear white, as their skeletons becomes visible, and they begin to starve.

Bleaching does not mean automatic death for corals. Given a chance to recover, some corals can bounce back, incorporating new zooxanthellae. However, with prolonged or repeated heating events, corals do not have a chance to recover, and with a lack of algae for too long, most corals will die.

Why Study Coral Bleaching?

Beyond their beauty and draw for tourism, coral reefs play an important role in the health of coastal ecosystems, supporting immense biodiversity, and providing important protection for coastlines from storm surge. With increasing frequency of marine heatwaves, including those predicted for this summer triggered by the most recent El Niño event, understanding coral bleaching and exploring how to mitigate its effects becomes critically important to the preservation of these ecologically, culturally, and economically valuable organisms.

Stories of Coral Bleaching

Scientists investigate the complexity of coral resilience against thermal stress

For scientists, what defines a coral species as stress-tolerant or stress-vulnerable is its mortality rate and recovery rate after a bleaching event. Coral species that are more resilient to heat stress may have some individuals die, but most will survive and recover from any bleaching. Stress-vulnerable coral species have a much more challenging time recovering from bleaching, resulting in more deaths, a decline of coral cover, and loss of habitats.

![A drone rests over a buoyant device. Under the drone is a coil of wires.]() Emerging technologies used to monitor coral bleaching in Guam, CNMI

Emerging technologies used to monitor coral bleaching in Guam, CNMI

With the threat of coral bleaching taunting the region, Pacific Islands are looking to emerging technologies for a quicker, more accurate assessment of the harmful impacts.

A project funded by the U.S. Geological Survey and PI-CASC is looking into testing NASA remote sensing technologies to determine if they are capable of more rapid assessments of coral bleaching over wide areas in the region. Over the years, natural resource managers had noted that local capacity building for coral surveying and monitoring was a challenge.

Pacific Islands brace for coral bleaching event

Coral reefs around the world are age-old providers and defenders of our livelihood. From cultivating food and medicine to protecting our shores from powerful storms, these ecosystems have proven to be vital resources on a global scale. Indigenous Pacific Island communities also find value in coral reefs, and their resources are often integrated into their cultures and traditions.

But a lingering threat to the vitality of these precious ecosystems remains: coral bleaching.

PI-CASC Projects Related to Coral Bleaching

Ecological and socio-cultural responses to transplanting corals to enhance reef resilience near Oʻahu

PI: Crawford Drury; FY 2021

The increasing frequency and severity of coral bleaching events means that human intervention is needed to support the adaptive capacity of reefs. This project proposes to identify the sources of resilience in two important reef-building species known to be more resilient to climate stressors, by temporarily transplanting specimen between six reefs in two bays of windward Oʻahu.

Identifying locations for coral reef climate resilience

PI: Monica Moritsch; FY2020

Coral bleaching events jeopardize coral reefs’ ability to continue to provide important ecosystem services and cultural value. This project aims to identify locations where resilience-based management strategies for reefs could have the greatest chance of success in Guam and American Samoa.

Using cutting-edge technology to assess coral reef bleaching events and recovery rates in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

PI: Romina King; FY2020

Multiple coral bleaching events between 2013 and 2017 impacted coral reefs in Guam and CNMI, resulting in the loss of more than a third of shallow living coral cover, with some species experiencing more than 90% mortality. This project assess new NASA remote sensing technology, MiDAR, to conduct rapid assessments of coral bleaching over a wide geographic area.

Mitigating climate change impacts: What drives thermal resilience in Hawaiʻiʻs coral reefs?

PI: Ruth Gates/Shayle Matsuda; FY2016

Corals, the bedrock of marine ecosystems, are particularly susceptible to the stressors of climate change. But species’ reactions vary. This study identifies biological characteristics that enhance coral thermal tolerance, for improved future management.

Coral adaptation and acclimatization to global change: Resilience to hotter, more acidic oceans

PI: Robert Toonen; FY2015

Excess CO2 in the environment causes ocean acidification with potentially severe repercussions for coral reefs and coastal societies. This work clarifies coral resilience mechanisms and evaluates potential for adaptation to future conditions.

Emerging technologies used to monitor coral bleaching in Guam, CNMI

Emerging technologies used to monitor coral bleaching in Guam, CNMI